The idea of making the commemoration of 16 June 1976 more relevant to where we live or where we are from, no matter where that is in South Africa, has always been tugging at my sleeves.

There was especially this sense that very little was being done to honour and commemorate those young struggle heroes from the Western Cape where I live and acknowledge their part in the 1976 student uprisings.

Each year I try to look at different things that can get us a little closer to this idea and this year I have come across an initiative that very much ties in with it. Added to that, I have also found my own personal way of commemorating the youth from my own area who have lost their lives shaping our collective future.

Finding the Hidden Histories

Based in Mowbray Cape Town, The Tshisimani Centre for Activist Education is launching an oral and documentary history project that will draw focus to how the 1976 Student Uprising unfolded in greater Cape Town.

The prevailing image that is portrayed when the student protests of 1976 are commemorated is that students in Soweto were the only ones protesting when in fact 1976 was a year in which an almost equally large number of people were killed by police in the Western Cape compared to Soweto and everywhere else in the country.

The centre draws its name ‘Tshisimani’ from a word in the TshiVenda language meaning fountain, spring or ‘at the water source'. This captures the driving inspiration for the Centre, which is to nourish, replenish and sustain the power and capacity of activist movements, organisations and networks engaged in grassroots struggle to build a just society in South Africa and internationally.

For millions of people worldwide, the uprisings of 1976 are most often associated with the events that took place in Soweto on June 16 when police opened fire on students marching to oppose the Apartheid policy of enforce Afrikaans as the medium of instruction in black schools.

For many that day is symbolised by Sam Nzima’s picture of 18-year-old activist Mbuyisa Makhubo carrying the slain Hector Pieterson in his arms.

Taking into account that the uprising did indeed start in Soweto, Bruinou.com has on previous occasions drawn attention to the fact that besides the Soweto students, scores of Cape Town youth and student activists were slain in 1976 along with many from other parts of the country.

Many who were not actively protesting but who were just in the wrong place at the wrong time were also killed by police.

Our 16 June 2014 article "They so easily say Get Over It" contains links to lists with the names of 400 people known to have been killed during riots and protests in 1976. There are also many who simply disappeared or whose bodies were never found.

The Tshisimani project wants to show that there is a larger story to the 1976 student uprisings.

The rebellion had spread across the country and by August 1976 had erupted in black and coloured townships in the Western Cape, starting with a student boycott at the University of the Western Cape and spreading across the Cape Peninsula.

It is this narrative that lies at the heart of an initiative of the Cape Town chapter of the Tshisimani Centre for Activist Education, which intends putting these events into perspective and crafting an authentic representation of the uprising in the Cape.

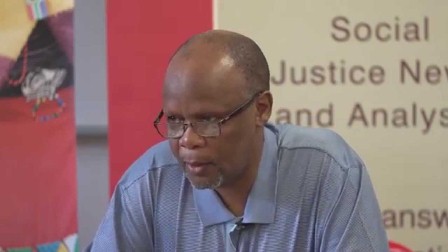

Dinga Sikwebu, a unionist affiliated with the centre, told Saturday Argus that this was part of a project “to excavate invisible and hidden histories. It is part of an agenda to move away from Soweto-centred versions of what was in actual fact a national uprising”.

“Through the project, the centre hopes to inspire other micro and local histories of the 1976 revolt.”

When the rebellion started, Sikwebu was a 15-year-old Form 2 student at Sizamile Secondary (now Oscar Mpetha High) in Nyanga. He considers this as the moment in which his life changed.

Sikwebu said there was a need to properly incorporate the history of 1976 in Cape Town.

“There is a very Soweto-centric approach in the whole of the 1976 narrative; understandably so. But if we are to learn anything from what happened 40 years ago, we must tease out what actually happened although the uprising began there, it also spread to other parts of the country and as it moved it took different forms in different areas,” Sikwebu said.

"There is a need to recognise everyone’s contribution to the Struggle."

"With only four high schools in black African townships and hundreds of coloured schools, what did it mean to take up a campaign on Afrikaans as a medium of instruction?"

“How did the thousands of Afrikaans-speaking students react to assertions that their mother-tongue was the language of the oppressor?"

“What jolted them to take part in the campaign with their counterparts in Langa, Nyanga and Gugulethu?”

The Rise of Solidarity

Dinga Sikwebu asks a question I have never consciously thought about but it turns out that perhaps I have known at least part of the answer all along.

Through the years as I grew up I have learned from individuals who were of the Western Cape Class of '76 who are all at least around 12 years older than I am, that their protests were not merely aimed at Afrikaans as a language or as an optional language of instruction. Afrikaans was after all their mother tongue. Their protesting was however aimed more at the enforcement of Afrikaans as the only language of instruction for black students whose mother tongue was not Afrikaans. It started as an act of solidarity.

Their protests were even more so aimed at fighting the entire system of Bantu Education, of unequal and separate education or as some would dub it, ‘Gutter Education’.

The protests in the Western Cape then grew from fighting the unequal distribution of resources in the separate education systems into an outright uprising against the entire system of Apartheid.

The rise of Black Consciousness amongst Coloured youth who far outnumbered their Black counterparts in the Cape Peninsula, saw a level of solidarity among them that has never been seen before and it was this solidarity that a few years later through the early 1980's essentially turned the Western Cape into a virtual epicentre of internal resistance against Apartheid.

The combined efforts of student movements, civic organisations, community and church leaders along with trade unions brought about numerous defiance campaigns and general strikes in the Western Cape.

All of these groupings working together had set a new tone for networking and solidarity that spread throughout the country and largely contributed to the establishment of the United Democratic Front.

It is this history of 1976 that needs to be told and should no longer remain shadowed by a disproportionate focus on only what had happened in Soweto.

The ultimate sacrifice made by so many in the Western Cape and in other parts of the country during 1976 should be honoured and commemorated as much as we should commemorate the lives of Hector Pieterson and all the many others who have losts their lives in Soweto.

We at Bruinou.com call on you to support and contribute information to the initiative by Dinga Sikwebu and The Tshisimani Centre for Activist Education.

We suggest that besides looking at 1976, each of us should find out as much as we can about what happened during the liberation struggle in our own areas, there wherever we live, no matter where it is in South Africa, including Soweto and make an effort to document and commemorate those forgotten names of each and every one who sacrificed their lives during 1976 and the many years before and after.

The information is out there but it gathers dust in archives and digital cobwebs on forgotten websites.

It is then also important that we should get today's youth to find out who the elders are in our communities that were in The Class of '76 and find out first-hand from them how the student uprisings affected them and what roles, if any, they had played in the events of that year, the years before and the years that followed.

Read Their Names Out Loud

Personally, I have decided to start a new 16 June tradition right here where I live in Elsies River and I am calling it Read Their Names Out Loud.

I am drawing up a list of names of people from my area whose lives were taken in 1976 and throughout the other liberation struggle years. Besides the five persons from my area (I know of) who were killed in 1976 I will also include the name of Johanna Moses shot dead in Elsies River on 16 June 1980 as well as Glenda Scheepers, Gavin Slavers, Andrew Christians and the several others shot dead in Elsies River over the next few days that followed 16 June 1980.

I knew none of them personally but I shall henceforth be Reading Their Names Out Loud, one by one, every year on 16th of June and hopefully each year I will find a public platform where I can do that.

I do not have all the names as yet but as I am writing this, my list is growing each and every time that I am looking into different resources for this article.

I am hoping that you too will adopt this tradition to honour the martyrs of your hometown.

Perhaps if we all bring 1976 closer to home, to where we live now or to where we are from, we and those around us will reignite a need to start taking greater responsibility in our roles of shaping the way our country is governed, shaping the way our economy functions and shaping the way the current generation of students are given access to resources.

A luta continua

Click Here to Search the TRC Reports on the SABC Website - Search using the name of your town, your area or district.

Click Here for the SAHistory.org Article Containing a List of People Killed in 1976.

Click Here to Read the Complete Saturday Argus Article on the Tshisimani Centre initiative.